Source: Capitaleconomics

Geopolitical context

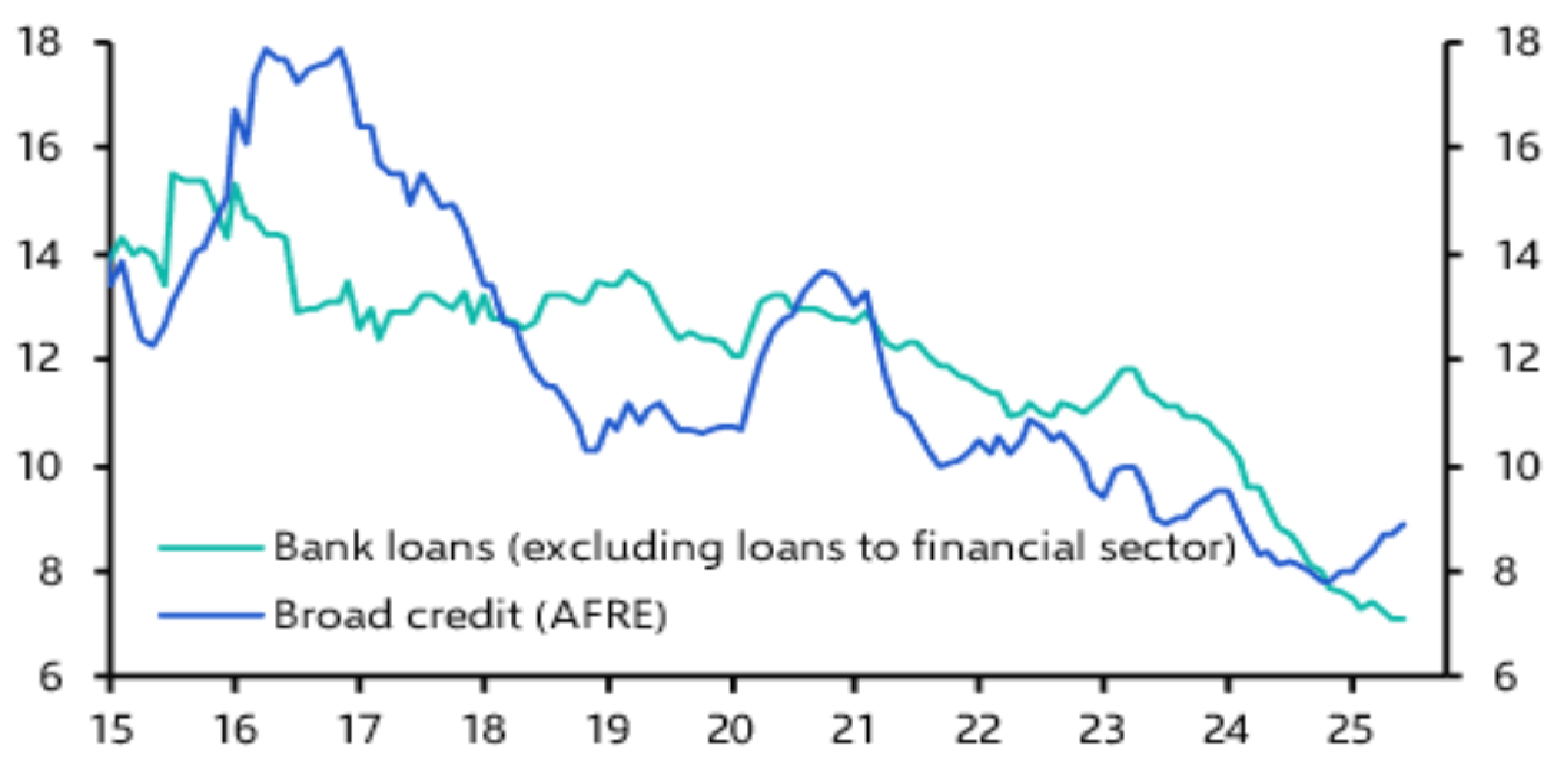

In the first half of 2024, Chinese banks experienced a sharp rise in non-performing loans from consumer credit, revealing cracks in the country's push to drive growth through household borrowing. As policymakers in Beijing grow increasingly concerned about domestic consumption, they’ve rolled out policies pressuring banks to extend more credit. However, the ground reality paints a more complex picture, where banks are struggling to find borrowers even as defaults accumulate.

Since March, regulators have issued a series of mandates aimed at encouraging personal lending, hoping to counteract the economic drag from ongoing tensions with the United States, particularly in trade and technology. These directives led to record-low interest rates for personal loans, in some cases dipping below 3%. However, as defaults mounted and margins thinned, banks were forced to raise rates again, reflecting growing concerns about risk and profitability.

Loan officers, managers, and executives across the banking sector describe an increasingly uneasy balancing act. It is getting more and more difficult to find borrowers for consumer loans as banks are caught between meeting lending targets and controlling bad loans. The pressure is so intense that some loan officers reportedly borrow from other institutions to meet quotas, an alarming sign of systemic strain.

Rising defaults

According to the Banking Credit Asset Registration and Transfer Center, Chinese banks put 74.27 billion yuan ($10.34 billion) of non-performing loans up for sale in the first quarter of 2025, a year-on-year increase of over 190%. Roughly 70% of these were personal loans. While the official non-performance loans ratio across all commercial banks remained steady at 1.51% by March’s end, it masks the real pain. Smaller regional banks reported these ratios exceeding 12%.

What’s more concerning is the trajectory. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the world’s largest bank by assets, reported a near doubling of its consumer NPL ratio to 2.39% at the end of 2024 from 1.34% a year earlier. The trend is clear: defaults are accelerating even among the strongest lenders.

This spike in delinquencies reflects deeper, structural issues. Wage growth has stagnated, especially in the state sector, manufacturing, and even finance which dents consumers' financial resilience. Simultaneously, fears over job security, partly due to U.S. tariffs and weaker industrial output, have prompted households to tighten their belts.

A survey by the People’s Bank of China shows this shift in sentiment: over 61% of households now intend to increase savings, a figure nearly 20 percentage points higher than pre-pandemic levels. It’s not that consumers can’t access cheap loans; many simply don’t want them.

Economic Ripples and Corporate Setbacks

The consumer lending crisis is unfolding against a broader backdrop of industrial slowdown and foreign investment recalibration. For instance, Volkswagen and its Chinese partner SAIC are shutting down their joint venture plant in Nanjing, a symbolic stronghold of German industrial presence in China. Production has already ceased, with operations being relocated amid shifting priorities and electric vehicle ambitions.

Volkswagen’s retreat is emblematic of broader economic shifts: foreign companies face declining market share and a cooling consumer base. The old economic model, built on aggressive production, investment, and export-driven growth, is increasingly clashing with the reality of overleveraged households and cautious spending.